A variety of tactics are being used to silence dissent in Uganda

As the 2026 elections loom, more sophisticated techniques are used to keep opposition at bay

Kizza Besigye, a 69-year-old physician and four-time presidential challenger, has long been a thorn in the side of Uganda’s ruling establishment. Now, once again, he is at the centre of a political storm. Hauled before a civilian court in Kampala, Besigye faces the most serious charge yet: treason, still punishable by death under Ugandan law.

To his supporters, it is a familiar script, another attempt to silence dissent. But this time, the prosecution has introduced something new: a web of online narratives, amplified across social media, that have been repurposed as evidence in court. What began as digital chatter has migrated into the legal system, raising questions about the role of manipulated content in shaping the fate of one of Uganda’s most prominent opposition figures.

For more than two decades, Besigye’s defiance has defined Ugandan politics. Once a close ally of president Yoweri Museveni and even his personal physician during the guerrilla war that brought him to power, Besigye broke ranks in 2000 with a scathing critique of corruption and authoritarianism. Since then, his presidential campaigns in 2001, 2006, 2011, and 2016 have ended in allegations of electoral fraud, arrests, violent crackdowns, and long stretches of house arrest. His battles with the state have become a constant backdrop to Uganda’s politics.

What makes the latest case different is not the charge itself – Besigye has faced treason accusations before – but the evidence being deployed. Authorities have leaned on alleged phone records and leaked audio recordings shared online, some of which analysts and fact-checkers have flagged as manipulated or AI-generated. Posts accusing Besigye of plotting to bomb the presidential jet, acquiring weapons abroad, or conspiring with Western sponsors first gained traction on X, TikTok, and Facebook before being cited by pro-government commentators and, eventually, state prosecutors.

As Uganda heads toward the 2026 elections, the Besigye case is more than just another courtroom drama. It offers a window into how digital manipulation is being weaponised by pro-government networks to target opponents, shift public opinion, and legitimise state repression.

Online attacks

In the months leading up to Uganda’s 2026 elections, a steady stream of social media posts has painted Besigye as a traitor plotting to destroy the state. The posts follow a familiar trend. First seed an allegation, amplify it through clusters of aligned accounts, and reinforce it with state-linked evidence.

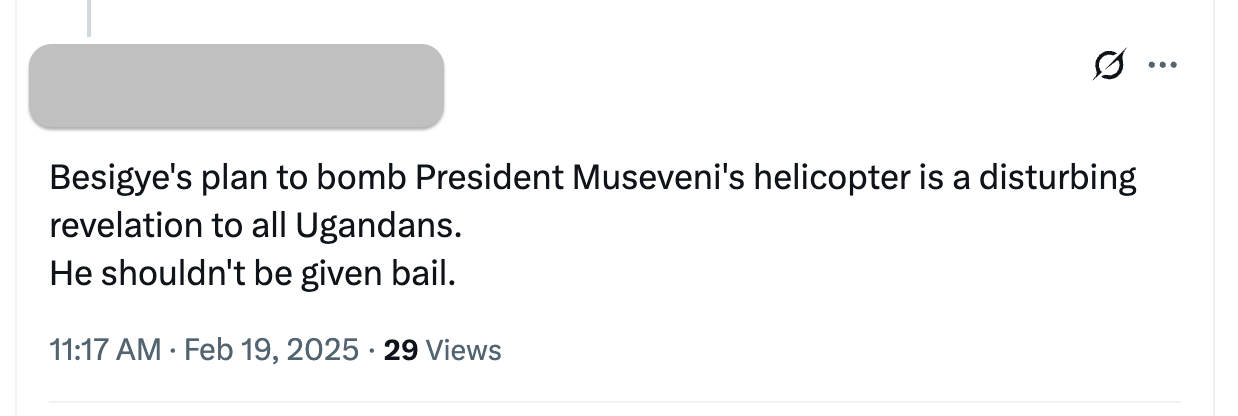

On 18 February 2025, the account @kezagloria44 posted: ‘I won’t join #FreeBesigye. There are recordings of him plotting to bomb the presidential jet.’

More than 114,000 people viewed it, and over 1,000 liked it. Within hours, the same account followed up, warning Ugandans that ‘national security is not a game’ and insisting that ignoring such threats could have ‘disastrous consequences.’

Other accounts joined in. @AkelloJM and @NamuliPasha echoed the charge, repeating that Besigye sought to acquire drones and target the president’s helicopter. They framed his detention as a necessary step to protect the nation. The volume of posts grew quickly. There were 68 between 15 and 25 February 2025 alone.

By 20 February 2025, the narrative had shifted from specific allegations to broader character assassination. @kezagloria44 declared that ‘past heroism does not excuse present betrayal’, a pointed reference to Besigye’s role as a Bush War veteran. The message was that, whatever his history, he had become an enemy of the state.

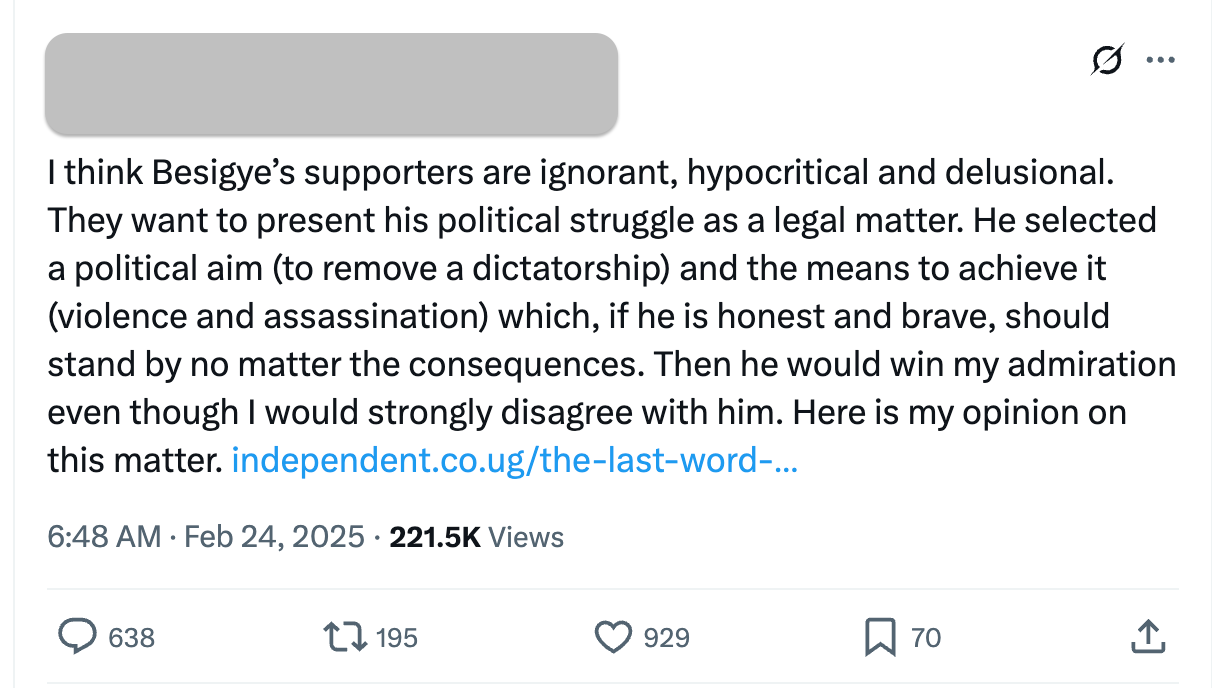

Prominent voices amplified these claims. Journalist Andrew Mwenda told his 220,000 followers that Besigye’s supporters were ‘ignorant, hypocritical and delusional,’ portraying Besigye as someone who had chosen violence and assassination as political tools. A post by @MwesigyeFranks, shared widely in November 2024, claimed that leaked audios showed Besigye conspiring with Western sponsors and disparaging rival opposition leader Bobi Wine. Even smaller accounts contributed, alleging that his family ties, including his son’s alleged sexuality, made him vulnerable under Uganda’s harsh laws.

Then came reinforcement from the state itself. On 30 May 2025, the newspaper Observer Uganda published details ‘inside state evidence,’ claiming Besigye had plotted to assassinate president Museveni using ricin, counterfeit currency, and drone attacks. Around the same period, the Independent in Kampala reported on 29 May 2025 that the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions’ summary cites testimony, travel logs and ‘recordings’, alleging requests for ricin and drone attacks against president Museveni. These themes had already circulated for months on X, seeded by accounts like @kezagloria44 and amplified across dozens of others.

Besigye’s fate is yet to be determined. He and his co-accused Hajjii Lutale boycotted the start of their treason trial on 01 September 2025. According to their lawyer, they refused to appear before a judge who was biased.

The judge in question, Emmanuel Baguma, denied the duo bail on 09 August 2025, after they had been held in prison for almost nine months.

Abduction and military court

Besigye’s current ordeal started after he and Lutale were abducted in Nairobi, Kenya, on 16 November 2024. He had travelled there to attend a book launch by Martha Karua, a prominent Kenyan politician and advocate (who would later join his legal team). But instead of a quiet literary event, the night ended in his capture.

Besigye’s wife, Winnie Byanyima, head of the United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), described his abduction and has called the detention politically motivated.

‘He’s been framed, and it’s not the first time he’s been framed,’ she said in an interview with the BBC in January 2025, adding that Museveni has tried numerous times to criminalise her husband.

‘Two little pistols were planted on him in Nairobi by his very abductors; it’s a travesty,’ she said. ‘It’s criminalising the opposition.’ She added that many other opposition leaders in Uganda have been criminalised in a similar way. ‘He [Museveni] cannot accept legitimate, credible opposition.’

Besigye was forcibly taken back across the border – a move condemned by human rights groups, including Amnesty International, as a violation of international law – and brought before the Makindye General Court Martial – a military court.

Byanyima said of Museveni ‘... that military court serves him, he is head of the army and he runs the army very personally.’

Museveni’s eldest son Muhoozi Kainerugaba is the chief of Uganda’s defence force.

A week after Besigye’s abduction, the leaked audio clip surfaced online, purportedly capturing him negotiating with Western sponsors to overthrow the government.

Fact-checkers, including influential Ugandan journalist Gabriel Buule with almost 168,000 followers, analysed the recording and found it 73% AI-generated, labelling it a deepfake. Kenyan activists like Khalid Hussein, executive director of human rights organisation VOCAL Africa, and Roland Ebole, regional researcher at Amnesty International, and opposition leaders, such as Betty Nambooze and Ssemujju Nganda, have denounced the audio as fabricated, accusing the government of using manipulated content to smear Besigye.

On 03 January 2025 the military court said Besigye and Lutale would be tried for treachery and they were remanded to Luzira Maximum Security Prison in Kampala.

On 31 January 2025, a landmark decision by Uganda’s Supreme Court declared that military courts could no longer try civilians. The case was eventually transferred to a civilian court. Although Besigye’s supporters wanted him freed immediately, he has been kept in the maximum security prison.

The #FreeBesigye hashtag was started on social media, most popularly on X, to have him released on bail. Although it attracted a large number of supporters and was trending online, the outcry wasn’t enough to pressure the government to release him.

Despite going on a hunger strike on 11 February 2025 and deteriorating in health, his bail requests have continually been denied, with courts citing the grave nature of the charges and fears he might interfere with investigations.

New law passed

On 16 June 2025, in direct contravention of the Supreme Court ruling, Museveni signed into law the controversial Uganda Peoples' Defence Forces (Amendment) Act, 2025, which grants military courts the power to try civilians.

Opposition lawmakers vowed to challenge this law in the Constitutional Court and there has been an international outcry against it. There are fears that this law will be used against opposition figures, including Besigye.

UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk said: ‘I am concerned that rather than encouraging efforts to implement the Supreme Court’s crystal-clear decision of January this year, Uganda’s legislators have voted to reinstate and broaden military court’s jurisdiction to try civilians, which would contravene international human rights law obligations.’

Besigye’s case has highlighted how digital and other tools can be weaponised to stifle opposition in Uganda.

His abduction from Kenya, facilitated by alleged coordination between Ugandan and Kenyan authorities, the release of inauthentic recordings and the use of military courts are all warning signs in the run-up to the elections.

These tactics fit a broader trend of digital manipulation in some of Uganda’s politics. Deepfakes and disinformation campaigns have become tools to undermine candidates, like Bobi Wine, with different sides exploiting technology to amplify their narratives.

This is not only happening in Africa, it has become part of European public life too: politicians fight each other in the virtual arena, and don’t shy away from using digitally generated fake content. Therefore, the story of Uganda’s opposition leader might be a cautionary tale for all of us.

This article was written by Edward Tumwine and Bella Twine, freelance journalists working with the Pravda Association, and edited by senior editor Eva Vajda.